August 25, 2018

The first thing I see as we cross the border from Poland to the Czech Republic is a cop thrusting a speeding ticket through the window of a young man’s dusty old 3-series. The youth seems resigned, the cop bored; it’s a routine transaction, Wile E Coyote clutching by the scruff of the neck, temporarily at least, a shrugging Roadrunner.

Moments later I’m negotiating some tricky hill-town twists and turns. I pull into a lay-by to consult that font of all travel wisdom, the satellite navigation system. A old man approaches, arms akimbo. He wags his finger. I point at my phone. He shakes his head. I shake mine more vigourously. “Park there, not here,” he says in a thick accent. I should know better than to allow these Victor Meldrews with too much time on their hands to rile me.

It colours my first impressions of the country: it’s a totalitarian regime; the people, secretly unhappy in their quiescence to the state, wreak vengeance on tourists.

The dystopia is further actualised when I visit Ostrava. Their industrial heritage is impossible to ignore, indeed the tourist board are attempting to make something of a virtue of it. Some architecture in the centre is pretty and historic, mainly early 20th century banks and theatres. But the city cowers in the shadow of a huge industrial giant named Vítkovice.

Apparently it’s the most visited tourist site in the Czech Republic outside Prague (I’m dubious because the taxi driver has never heard of it. He barks Czech instructions into Waze, gripping the phone with one hand and the steering wheel with the other. He stops the car in the middle of a long empty road. Huge red brick walls tower over us.

“Good, ja?”

“Err no. Bar? Cafe?”

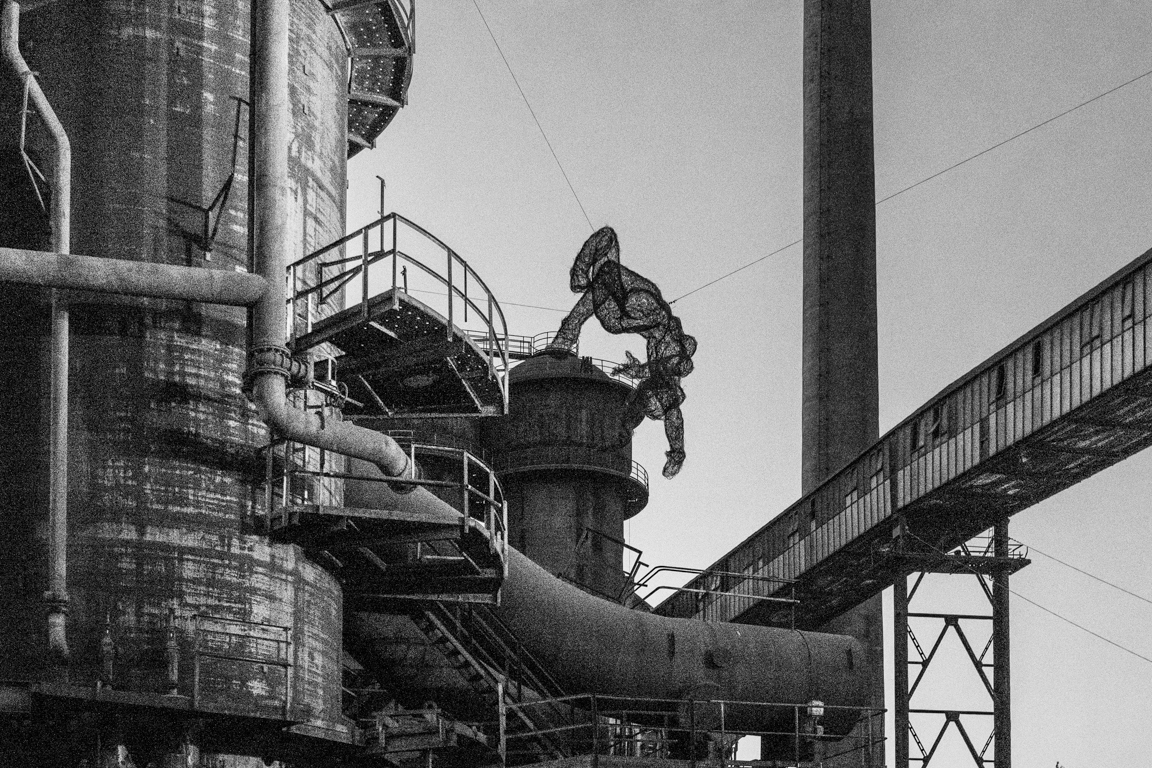

Either the Taxi driver was rogue or the conversation in German (consisting solely of nouns) got lost in translation because there is no missing the behemoth. An enormous glass tower, recently built on top of the original blast furnace, is the highest geographical point in Ostrava; it studs the dusk sky like a diamond lain on velvet. Flaking iron pipes pierce the troposphere. Walkways and conduits criss-cross crumbling concrete buildings.

It’s a curiously schizophrenic mixture where old meets new, youth meets maturity, prosperous meet penniless. The original gas holder, a beautiful spectre from days of old, has been lovingly restored into a modern conference centre; it now hosts student lectures, international conferences, and exhibitions. A middle aged gentleman reads a book underneath a labyrinth of concrete and iron; a piece of graffiti decorates the wall to his right while a couple of teenage girls enjoy prinks on the steps in front. A large man with a large gold watch smoking a large cigar presses some buttons on a machine; out blasts a kitsch rendition of The Stones’ Satisfaction. It’s perfect.

As in all cities, when night falls, the youth rise. By 11pm the place is teeming. A space carved out underneath the rats nest acts as a makeshift nightclub. There is something about post-industrial towns (Leeds and Sheffield are the same) that breeds ill behaviour. The boys arrive drunk. The girls arrive drunk. One man urinates from the subway into the road. The drinking continues. It’s time to leave. The city is trying to beautify the utilitarian but the younger generation clearly need time to develop a sophistication to match.