October 1, 2018

“Of course, I don’t like everything in Hungary.”

The mum in front of me is looking into the middle distance, as if seeking affirmation from a faraway muse. Around us, her two tearaway sons are tugging a poor, bedraggled dog around the forest. Her dark, piercing eyes return to mine.

“But it’s home. I’ve come back to make it work,” she says.

The strength and meaning of her words are beyond doubt but something rings hollow. It’s the sort of thing you say to convince yourself you’ve made the right decision. She has, it must be said, made an enormous relocation, trading her career in the US for life back home. But this angst from the educated urbanites of Budapest is something that I will frequently witness over the next fortnight.

On the way into town, the public transport system befuddles me.

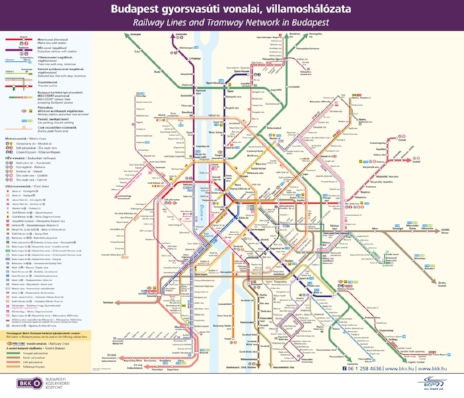

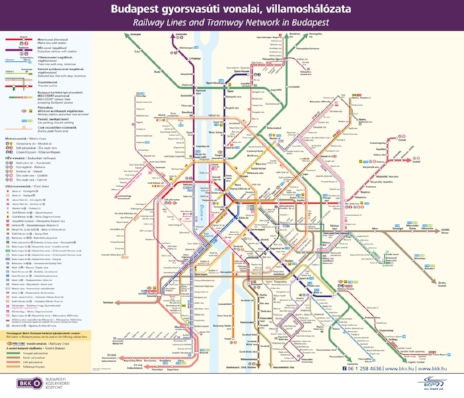

The transport map is a piece of fine art from the hand of a toddler, the kind only a parent could decipher. Multicoloured lines apparently notating tram circuits, bus routes, and metro lines decorate the page.

When a bright yellow tram rattles towards me and shudders to a halt, I jump on. Quite where it’s going is anyone’s guess. Fortunately it is city-bound.

Onboard, people are jammed up next to each other but it’s good humoured. Everyone is smiling, everyone is friendly. I’m taken off-guard. I’d assumed Budapest was another Bratislava, a small, growing city. But it’s not. It’s huge.

I chat to a young German couple. The young man is studying urban planning, investigating how to make cities more liveable, how to balance diversity and size of population with infrastructure and housing. Germany, where he lives, is not like the UK where a single city is dominant; there are a few large cities that make the country quite well balanced – Berlin, Hamburg, Munich. As for Hungary, a third of the population live in Budapest. A third! It’s Hungary’s London, a huge black planet that tries to pull everything into its orbit unless some equally powerful force counters it.

Like London, the river helps triangulate you (you’re either on the Buda side, or you’re on the Pest side) and it’s from here where two essential landmarks can best be viewed. From the Pest side, you’re treated to huge skies with clouds scurrying behind the Buda castle. It’s so pretty that a fellow photographer puts down his camera, sits on a bollard, and marvels at the pastel colours.

If you’re quick you can enjoy a double bill. There’s a moment just before the sun disappears behind the Buda hills in the evening where a golden light bathes the parliament building in the last rays of the day. Tourists and locals alike gather to watch the spectacle.

You can’t help but be enchanted, not only by this but by all that the city has to offer. The rich tapestry of Budapest’s history is woven throughout the city from the largest synagogue in Europe to the neo-Gothic splendour of Fisherman’s Bastion. Influences range from Roman to Ottomon, architectural styles from Renaissance to Art Noveau. This city has played a leading role throughout the ages.

On the tram on the way home I meet Hanna, an IT project manager. I’m still slightly in awe and I tell her what a beautiful city she lives in. She sighs. “Yes, it is. Very beautiful. But there are ugly things happening in this country. The government, you know.” Her voice trails off; she is visibly sad. She is planning to leave for Austria.

Herein lies the problem. The city possesses everything it needs to be world class – history, culture, arts, music, architecture. Many top technical companies such as Vodafone and IBM already thrive on the technology park attached to the University. But the life-force that courses through city is not its river, mighty though the Danube is. A city lives and dies by its residents and many people in Budapest are disenchanted. Orbam has all the local media in his pocket to ensure his influence in rural seats. But an incompetent and divided opposition also allowed his Fidesz party to pick up 12 from 18 seats in Budapest, a traditional stronghold for the left. The 2018 election was a disaster for many in the capital and, unlike the mother of two with the unenviable pressures of a young family to raise, many of the young middle class like Hanna simply don’t have “to make it work”.

Pushed by an extreme right-wing Government on one side, pulled by liberal-minded cities like Stockholm, Berlin and Oslo on the other, they are gunning down the highway out of Budapest as quick as they can. A final glance in the rear-view mirror reveals the Parliament that has abandoned them fast becoming a blur as they bid their adieus.