August 24, 2018

From the sweat inducing streets a sign beckons: Krakow Pinball Museum. We um and ah. It’s not really the cultural experience we sought in Krakow. But it’s air-conditioned. They serve cold drinks. Dogs are welcome.

We descend the stairs into an underground cellar type space. It’s like entering an amusement arcade from the 80s except you don’t need a stash of 10 pence pieces bursting from one of those crappy plastic moneybags. Instead you exchange your entrance fee for one of those festival-style wristbands. This allows you to enter and re-enter the place all day long. The machines are all free-play.

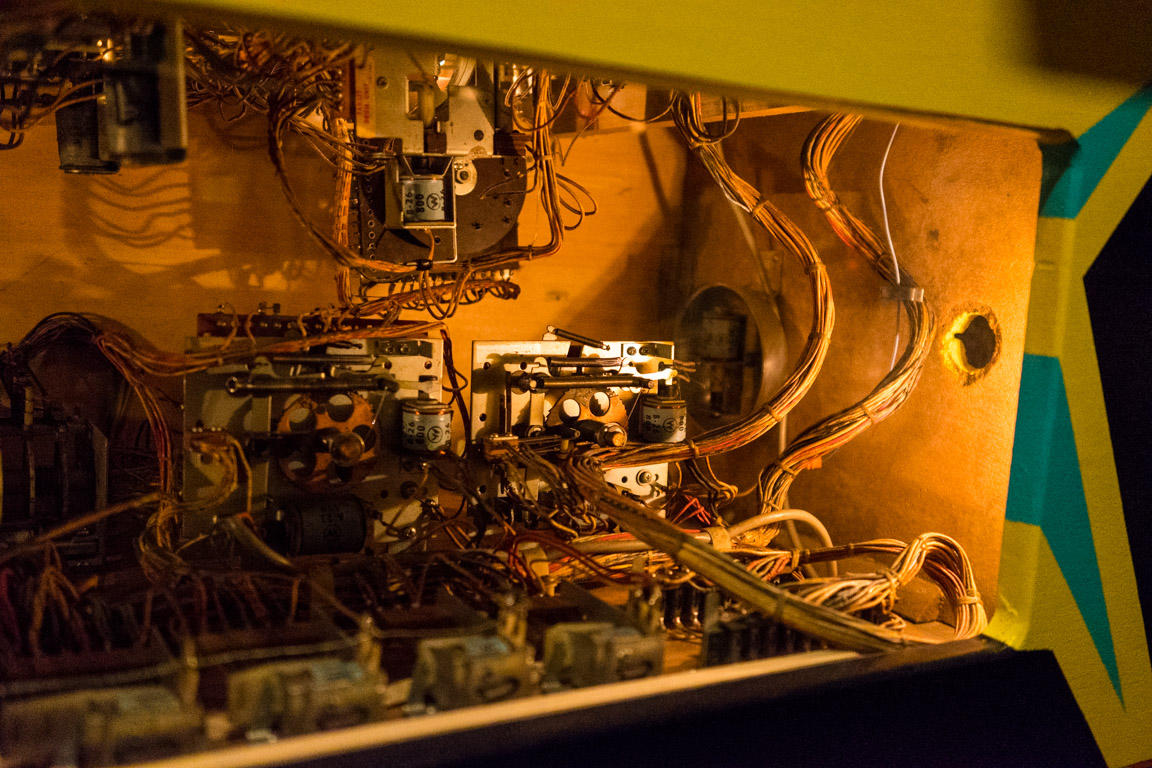

We spend a highly enjoyable few hours here in sweet air-conditioned bliss. The oldest machine I discovered was Jolly Roger (1967, Williams). The scoreboard on these old machines is mechanical and they roll over like the milometer on your car with a satisfying click. The museum housed it in a transparent case so you can see all the switches, relays, bells and whistles that animate these electro-mechanical creatures of old.

Pinball machines remained pretty simple devices throughout the early to mid 70s. Wizard (1976, Bally) is one of Bally’s last electro-mechanical machines. It features some really great artwork from Dave Christensen with stylised depictions of Ann Margret and Roger Daltrey from the Ken Russel screen adaptation of the classic rock opera.

Like the rest of the industry, Bally would soon move to solid state technology in an attempt to defend itself from its own Creature From the Black Lagoon (1992, Midway). Video games, which were more lucrative and cheaper to maintain, incited (panicked) creativity and innovation from the 80s onwards. Xenon (1980, Bally), the first talking pinball table by Bally, set the precedent. Brighter lights, louder noises, computerised scoring, mini games were soon to follow. It’s hardly surprising. They were screaming for attention from the corner of the room over the wacawacawaca drone of the Pacman machine throughout the golden age of arcade games.

It’s more of a surprise that they survived at all. By the 90s they were technological marvels of modern engineering, designed to ensnare the sophisticated home video gamer and keep their coins flowing. I remember The Adam’s Family (1992, Midway) from afternoons wiled away in Leeds Met University Student Union Bar. My ability to comprehend it even then was zero, beyond simply hitting the flippers and trying to keep the ball alive. It wasn’t cheap and my skill was woeful so I played it rarely. Free play (offered here at the Krakow Pinball Museum), on the other hand, is an opportunity to unearth pinball machine secrets without it costing the earth. Shoot The Thing to gain multiball? Let me try that (again. And again).

We meet the owner and his family. He maintains all the machines himself. “I need to find someone who I can train to do the work,” he says. The skills no longer exist and neither, it seems, does the desire. It’s a shame because without it the museum will whither and the joys of this cultural pastime will be confined to the history books. Be sure to visit if you’re in Krakow. Go play a mean pinball before it f-f-fades away.